Assessment and feedback

Feedback for Part 1 - Core Concepts

End of Part 1 - Core Concepts

TA Kush

‘The Lady of the House, Ta-Kush, Daughter of Osiris, Pa-Muta; her mother Lady of the House, Shay’

THE MAIDSTONE MUSEUM EGYPTIAN MUMMY

An account of the Ta Kush paleoradiological investigation.

James Elliott - Last updated March 2022

Computed Tomography scan of Ta Kush

The history behind the ancient Egyptian mummy at Maidstone Museum is very interesting indeed. The following is an extract from the museum's website:

Her 2,700 year old mummy was brought to England in the 1820s. This originally had an inner and outer coffin, but only the inner wooden coffin reached the museum in the 19th century. In 1843, she was unwrapped and studied by Samuel Birch of the British Museum, and a local doctor, Hugh Welch Diamond. She was then presented by Dr Diamond to his cousin, Mr Charles, whose collections formed the Charles Museum in Maidstone. The Charles Museum later became Maidstone Museum after Charles’ death.

In July 2016, the Museum received a grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund for an exciting project to redisplay ancient Egyptian and Greek artefacts in a new ‘Ancient Lives’ Gallery, which opened in October 2017. As part of the redisplay, the Museum worked with the Kent Institute of Medicine and Science (KIMS) and FaceLab at Liverpool John Moores University to conduct a CT scan and facial reconstruction of Ta-Kush, helping determine how she looked during her lifetime.

In November 2016, Ta-Kush made the short journey across Maidstone to KIMS to undergo a full body scan. This revealed a number of fascinating finds about the mummy, as well as other mummified remains in the museum’s collections, which were also scanned.

Source: https://museum.maidstone.gov.uk/explore/collections/ancient-egyptians/ta-kush-lady-house/

Findings of the autopsy, from 1843, were published by Hugh W. Diamond in 1846 (available here and shown below).

Author's comment

The CT scan of Ta Kush provided some great advertisement material for both the museum and KIMS hospital. Although the video below provides a good overview of what happened it should also be mentioned that two scans were performed: (1) a whole body (including sarcophagus) scan and (2) a head/face scan, including the majority of the cervical spine.

The radiographer scanning the mummy, Mark Garrad, told me that the CT scanner was screaming with all its electrical might to not over-irradiate the 'patient'. Normally we would not scan head-to-toe and certainly not at the greatest resolution possible, as this would incur a significant radiation burden. With the various alarms disengaged or ignored, Mark obtained two very detailed scans of the mummy. The result was two very large DICOM files, the format used for medical imaging. One benefit of CT DICOM files is the ability to reconstruct the data to view the 'patient' in different ways, for example either as a 3D reconstruction or specific areas of anatomy.

What to do with the CT data?

After the scan was completed the mummy went back to the museum, the data was kept on the imaging system at KIMS and a copy was sent to IMPACT mummy database (found here) and FaceLab at Liverpool John Moore's University. Andrew Nelson, a Professor in anthropology at Western University (Ontario, Canada, profile here), examined the CT data and provided an informal report on the condition and biological profile of Ta Kush. Among other findings, the estimated age at death was greatly increased from 14 years old due to the presence of erupted teeth, plaques within surviving arteries and the lack of growth plates in the skeleton. From the museum's point of view the CT data provided a wealth of visual information about Ta Kush to put on display for the benefit of the public. The icing on the cake was the facial reconstruction, providing an indication of what she looked like.

The staff from Facelab at Liverpool John Moore's University published an article in Digital Applications in Archaeology and Cultural Heritage. The link to the article can be found here, although you will need to pay for access (or ask your library for a copy). The reference and abstract are shown below:

Smith, K., Roughley, M., Harris, S., Wilkinson, C. and Palmer, E. (2020) 'From Ta-Kesh to Ta-Kush: The affordances of digital, haptic visualisation for heritage accessibility', Digital Applications in Archaeology and Cultural Heritage, 19, pp. e00159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.daach.2020.e00159

Abstract:

"This paper describes the 3D facial depiction of a 2700-year-old mummy, Ta-Kush, stewarded by Maidstone

Museum, UK, informed by new scientific and visual analysis which demanded a complete re-evaluation of her biography and presentation. The digital haptic reconstruction and visualisation workflow used to reconstruct her acial morphology is described, in the context of the multimodal and participatory approach taken by the museum in the complete redesign of the galleries in which the mummy is displayed. Informed by contemporary approaches to working with human remains in heritage spaces, we suggest that our virtual modelling methodology finds a logical conclusion in the presentation of the depiction both as a touch-object as well as a digital animation, and that this ‘digital unshelving’ enables the further rehumanization of Ta-Kush. Finally, we present and reflect upon visitor feedback, which suggests that audiences respond well to interpretive material in museums that utilizes cutting-edge, multimedia technologies."

How did I get involved?

I worked at KIMS Hospital as a diagnostic radiographer during the time of the scan. Incidentally, I was also studying MSc Forensic Radiography and I had my background in bioarchaeology from my Bachelors degree with Newcastle University. In 2018 I wrote a short article concerning the use of forensic radiography in archaeology for the professional magazine Imaging and Therapy Practice. As I was aware of the CT data from KIMS hospital, I approached the museum and asked for permission to use some of the images for the article to illustrate some key points (available here). In truth, it gave the article a sense of authenticity and intrigue rather than illustrate key points but at least it got the front cover.

I had the CT data on my PC, so I began to explore the mummy - digitally - to find out more about her preservation state, the presence of packing materials and any pathologies/trauma. This linked nicely into my studies about using medical imaging to reconstruct the biological profile of the deceased. I was about to start my MSc thesis to look at the use of CT in mummy studies, and whether there was a systematic approach used or whether it was more haphazard. With the data from the Ta Kush scan at hand I gained a greater understanding of how the method of CT scanning could impact upon image quality - and therefore diagnostic value.

Paul Lockwood, a fellow lecturer at Canterbury Christ Church University, then invited me to give a guest presentation at the Society of Radiographers South East Regional Study Day (November, 2018). The topic was paleoradiology, with a specific instruction to share my interests and research into mummy CT scans. After giving the presentation Paul suggested examining the CT head/face data with the intention of presenting the findings in an academic journal. We teamed up with Andrew Nelson and Samantha Harris (from the museum) and subsequently published our findings in the British Journal of Radiology - Case Reports (available here and shown below).

The main findings:

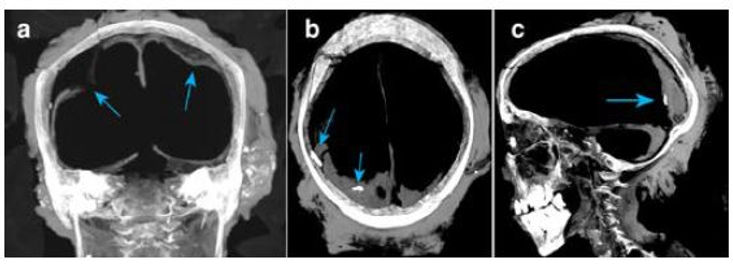

The skull has large post-mortem fractures / damage - A portion of the skull is broken, on the right side. These were not the result of injuries in life or the cause of death, but instead appear to be post-mortem (after death). It is unclear whether the damage has occurred due to her time in ownership (curatorship?) within England or perhaps in antiquity. The fractures are not mentioned within the autopsy report by Diamond in 1846, which state 'a rough cut had also been made partially through the folds of the bandages over the chest by the Custom-house authorities, in order to ascertain if the package contained any contraband articles'. Examination of the CT scan also demonstrates areas of bone loss within the skull, either by bone thinning or general loss of density. Again, this may demonstrate a pathological change or perhaps taphonomic changes during her 2,700 years in existence.

Brain matter found within the skull - The brain had not been removed during the mummification process. Many textbooks will recount how the Egyptians performed the gruesome task of taking the brain out through the nose, however the technique was not ubiquitous. A few high density objects, probably fragments of bone, litter the inside of the skull. These are most probably the result of either the autopsy by Diamond (1843) or HM Revenue and Customs searching for contraband when the mummy was imported in the 1820's.

The eyes were replaced with high density objects and packing material - Visual inspection of the mummy shows that the eyelids are closed and it is not possible to see evidence of the packing material or high density objects (unless an autopsy is performed). One of the other benefits of CT is that the internal structure of the mummy can be seen without having to perform an autopsy - this is termed as a non-destructive investigation. The CT scan shows two oval objects, one in each eye, supported with packing material to hold them in the position of the pupils. Such use of objects in ancient Egyptian mummies are not uncommon.

There are other findings too, such as the preservation of the teeth. From initial investigation it appears as though Ta Kush was a fully grown adult, with a full complement of teeth (although some have since become dislodged). The teeth show signs of decay and wear, although this is not surprising due to the high amounts of grit encountered with a diet mostly consisting in cereals (as was common in ancient Egypt). Whilst the amount of wear might be useful to age an individual in modern societies, it would not be accurate for past populations due to the change in diet. A full account of her dental status has not yet been made.

What next?

The next step is to investigate the whole-body scan of Ta Kush. Further information will be added to this page as results are disseminated.

Photographs and CT imaging are subject to copyright. Reproduced with kind permission from Maidstone Museum.